Developing the structure

In the previous chapters, we defined our domains, which are as follows:

SportNewsServicePoliticsNewsServiceFamousNewsServiceRecomendationServiceUsersService

The first step is to choose a domain to apply our techniques. To do this, we will use the UsersService. This domain is quite interesting because it has unique characteristics and is an excellent case to apply the techniques learned here.

Let's gather the tools that we will use for the composition of UsersService. At first, we will use only one database table, but we know that the rest will be created.

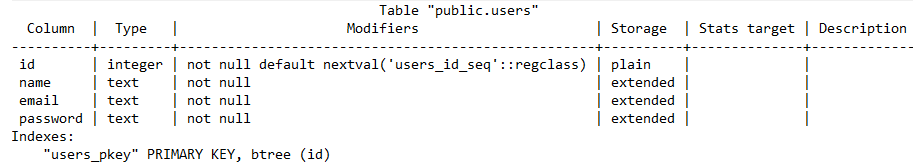

Database

Our database is a PostgreSQL and the structure of the first table is extremely simple, as seen in the following screenshot:

In the table users, we have an ID that is the unique identification key, username, user email, and user password.

Programming language and tools

Our UsersService will be written in Go; the tools we use in this programming language have already been described in Chapter 2, The Microservice Tools. However, it is necessary to download the dependencies of the project to start development. This is done using the following commands:

$ go get github.com/gorilla/mux

$ go get github.com/lib/pq

$ go get github.com/codegangsta/negroni

$ go get github.com/jmoiron/sqlxMuxer is responsible for application handles and is our initial dependency. The gorilla/mux will be responsible for the UsersService synchronous communication layer, at first. This communication will be with HTTP/JSON.

The PQ is the interface responsible for communication between our software and the PostgreSQL database. We will have a look at how it functions in this chapter.

The Negroni is our middleware manager. At this stage of the application, the sole responsibility is to manage the application logs.

The SQLX is our executor of queries in the database and since this is very common in Go, it'll be no different to use in ORMs in our microservice. However, the application of the values returned from the queries about our structs will be run by SLQX.

Project structure

The main characteristic of microservices is their simplicity of structure. This simplicity does not mean the absence of robustness, but it means it is easy to read and understand the project development.

Our UsersService is also simple enough to make future modifications. You can be sure that this project is going to change a few times in your life cycle.

The structure of our project in the first version is as follows:

models.goapp.gomain.go

Let's see each of them and how they function.

The models.go file

Starting with the models is always interesting, because it is the best place to understand the business of a project.

At first, we declare the package on which we are working, and then the imports required for the project, as follows:

package main

import (

"github.com/jmoiron/sqlx"

"golang.org/x/crypto/bcrypt"

) Then, we make the declaration of our entity, Users. Go does not have classes, but instead uses structs. The final behavior is very similar to the OOP, of course, but there are peculiarities.

Useris the struct responsible to represent the database entity:

type User struct {

ID int `json:"id" db:"id"`

Name string `json:"name" db:"name"`

Email string `json:"email" db:"email"`

Password string `json:"password" db:"password"`

} So, we have created the five basic CRUD operations, specifically: five-create, read one, read list, update, and delete.

- To get a return, just update the

Userinstance with the data fromdb:

func (u *User) get(db *sqlx.DB) error {

return db.Get(u, "SELECT name, email FROM users WHERE id=$1",

u.ID)

} The get method returns only one user. The data to search, in the case of the ID, is passed inside the memory reference of the struct, as can be seen by the syntax, u.ID. Something interesting to note here is that access to the database in PostgreSQL is through dependency injection, passed as a parameter in the get method.

- Update the data in the

dbusing the instance values:

func (u *User) update(db *sqlx.DB) error {

hashedPassword, err := bcrypt.GenerateFromPassword(

[]byte(u.Password),

bcrypt.DefaultCost,

)

if err != nil {

return err

}

_, err = db.Exec("UPDATE users SET name=$1, email=$2,

password=$3 WHERE id=$4", u.Name, u.Email,

string(hashedPassword), u.ID)

return err

} The update method is very similar in structure to the get method. The values for persistence are passed within the pointer *Users, and access to the database is for dependency injection. In addition to the query, which is obviously different from the query in the method get, there is the mechanism to crypto the password. To ensure that the password does not get exposed in the database, we use the bcrypt Go library to create a hash from the password passed to the method.

- Delete the date from the

dbusing the instance values:

func (u *User) delete(db *sqlx.DB) error {

_, err := db.Exec("DELETE FROM users WHERE id=$1", u.ID)

return err

} The delete method has the same structure as that of the get method. Note the _, err := db.Exec(...) declaration. This type of syntactic construction may seem strange, but it's necessary. Go does not throw an exception; it simply returns an error if it exists. This type of control seems absurd, but you can see that there is a lot of elegance in this code structure.

- Create a new user in the

dbusing the instance values:

func (u *User) create(db *sqlx.DB) error {

hashedPassword, err := bcrypt.GenerateFromPassword(

[]byte(u.Password),

bcrypt.DefaultCost,

)

if err != nil {

return err

}

return db.QueryRow(

"INSERT INTO users(name, email, password) VALUES($1, $2, $3)

RETURNING id", u.Name, u.Email,

string(hashedPassword)).Scan(&u.ID)

} In the update method, we make the treatment of password for insertion in the database, as shown in the following code:

Listreturns a list of users. This could be applied pagination:

func list(db *sqlx.DB, start, count int) ([]User, error) {

users := []User{}

err := db.Select(&users, "SELECT id, name,

email FROM users LIMIT $1 OFFSET $2", count, start)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return users, nil

} Finally, the most different point within our model. Primarily because list is not a method, but a function, this type of approach is common among Go developers. A method is only created if you change or use something of an instance or struct. When there is any type of alteration or use of data which creates a function, the list function simply returns a list of users receiving parameters for possible information paginations.

Finally, our archive, models.go, is as follows:

package main

import (

"github.com/jmoiron/sqlx"

"golang.org/x/crypto/bcrypt"

) User is the struct responsible for representing the database entity:

type User struct {

ID int `json:"id" db:"id"`

Name string `json:"name" db:"name"`

Email string `json:"email" db:"email"`

Password string `json:"password" db:"password"`

} Get returns just the update User instance with the data from db:

func (u *User) get(db *sqlx.DB) error {

return db.Get(u, "SELECT name, email FROM users WHERE id=$1",

u.ID)

}Update the data in the db using the instance values:

func (u *User) update(db *sqlx.DB) error {

hashedPassword, err := bcrypt.GenerateFromPassword(

[]byte(u.Password), bcrypt.DefaultCost)

if err != nil {

return err

}

_, err = db.Exec("UPDATE users SET name=$1, email=$2,

password=$3 WHERE id=$4", u.Name, u.Email,

string(hashedPassword), u.ID)

return err

} Delete the date from the db using the instance values:

func (u *User) delete(db *sqlx.DB) error {

_, err := db.Exec("DELETE FROM users WHERE id=$1", u.ID)

return err

} Create a new user in the db using the instance values:

func (u *User) create(db *sqlx.DB) error {

hashedPassword, err := bcrypt.GenerateFromPassword(

[]byte(u.Password), bcrypt.DefaultCost)

if err != nil {

return err

}

return db.QueryRow(

"INSERT INTO users(name, email, password) VALUES($1, $2, $3)

RETURNING id", u.Name, u.Email,

string(hashedPassword)).Scan(&u.ID)

} List returns a list of users. This could be applied pagination:

func list(db *sqlx.DB, start, count int) ([]User, error) {

users := []User{}

err := db.Select(&users, "SELECT id, name,

email FROM users LIMIT $1 OFFSET $2", count, start)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return users, nil

} The app.go file

The file app.go is responsible for receiving data and sending it to our data storage. When we read this file, it seems to do too much or is badly divided, but it is very important to understand the characteristics of the language with which we are working.

Go is an imperative programming language—just writing clear, simple, and objective code is the focus of the developers. Patterns like MVC projects and complex structures of settings are not always applied in Go, especially when you program in the purest way possible. This does not mean that such patterns cannot be applied, quite the contrary. However, patterns like MVC are used in the structures of the Go files, only when there is a real need.

Let's take a look at our file app. go. Again, we have the declaration of the package where we are working and the imports that will be used in the file:

package main

import (

"database/sql"

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"log"

"net/http"

"strconv"

"github.com/codegangsta/negroni"

"github.com/gorilla/mux"

"github.com/jmoiron/sqlx"

_ "github.com/lib/pq"

) There is a point of attention on imports, Imports _ "github.com/lib/pq". The underscore sign before import means that we are invoking the init method inside of this library, but we're not going to make any direct reference to the library within the code.

Similar to the file models.go, we have a declaration of a struct. Struct App is composed of two elements—a memory reference to the SQLX and a memory reference to our router.

App is the struct with app configuration values:

type App struct {

DB *sqlx.DB

Router *mux.Router

} The first struct method, App, is the Initialize. In our case, we've already got the connection with the database instantiated.

Initializes create the DB connection and prepares all the routes:

func (a *App) Initialize(db *sqlx.DB) {

a.DB = db

a.Router = mux.NewRouter()

a.initializeRoutes()

} After initializing the connections, it's now time to define the routes in the initializeRoutes method, as follows:

func (a *App) initializeRoutes() {

a.Router.HandleFunc("/users", a.getUsers).Methods("GET")

a.Router.HandleFunc("/user", a.createUser).Methods("POST")

a.Router.HandleFunc("/user/{id:[0-9]+}",

a.getUser).Methods("GET")

a.Router.HandleFunc("/user/{id:[0-9]+}",

a.updateUser).Methods("PUT")

a.Router.HandleFunc("/user/{id:[0-9]+}",

a.deleteUser).Methods("DELETE")

} The definition of the routes is very clear and simple, because it is a simple CRUD. The following is the method that will be used to initialize the microservice. The Run method activates the Negroni, which is our controller of middleware, passes the router to it, and activates the server Go native.

Run initializes the server:

func (a *App) Run(addr string) {

n := negroni.Classic()

n.UseHandler(a.Router)

log.Fatal(http.ListenAndServe(addr, n))

} To avoid code duplication, let's create two helper functions inside the App.go file. These functions are respondWithError and respondWithJSON. The first function is responsible for passing to the HTTP layer, error codes that can be generated within the application, such as 404, 500, and all codes that should be reported.

The second function is responsible for creating the JSONs that must be answered for each request:

func respondWithError(w http.ResponseWriter, code int, message

string) {

respondWithJSON(w, code, map[string]string{"error": message})

}

func respondWithJSON(w http.ResponseWriter, code int, payload

interface{}) {

response, _ := json.Marshal(payload)

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json")

w.WriteHeader(code)

w.Write(response)

}Now, let's create our CRUD methods. The first method that we'll create will be responsible for fetching a single user; let's call it getUser. This method will translate the last ID in the request by checking if it is possible to be used for searching in the database. If it is not possible to throw an HTTP error, a User instance is created, and the get method of the model is called. If the user is not found in the database, or if there is any kind of problem with the database, the corresponding HTTP error code will be sent. In the end, if everything's okay, JSON will be sent in response to the request:

func (a *App) getUser(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

vars := mux.Vars(r)

id, err := strconv.Atoi(vars["id"])

if err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusBadRequest, "Invalid

product ID")

return

}

user := User{ID: id}

if err := user.get(a.DB); err != nil {

switch err {

case sql.ErrNoRows:

respondWithError(w, http.StatusNotFound, "User not found")

default:

respondWithError(w, http.StatusInternalServerError, err.Error())

}

return

}

respondWithJSON(w, http.StatusOK, user)

} The next method of the app.go file has a purpose much like the getUser. However, we want to get many users at once. Let's call this the getUsers method. This method receives count and starts as parameters to search pagination, normalizing the possible values of a misguided search. Then, it uses the list method, which is in the models.go file, and passes in the instance of the database connection and the values for search pagination. If we do not have any mistakes, we send the JSON in response to the request:

func (a *App) getUsers(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

count, _ := strconv.Atoi(r.FormValue("count"))

start, _ := strconv.Atoi(r.FormValue("start"))

if count > 10 || count < 1 {

count = 10

}

if start < 0 {

start = 0

}

users, err := list(a.DB, start, count)

if err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusInternalServerError, err.Error())

return

}

respondWithJSON(w, http.StatusOK, users)

} Now, we move on to the methods that generate changes in the database. The first method that we see is createUser. In this method, we translate JSON into the body of the request sent to an instance of the user. The user instance calls the create method of the model to persist the data. If no error occurs, the HTTP 201 code is not returned, indicating that the user was created successfully:

func (a *App) createUser(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var user User

decoder := json.NewDecoder(r.Body)

if err := decoder.Decode(&user); err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusBadRequest, "Invalid request payload")

return

}

defer r.Body.Close()

if err := user.create(a.DB); err != nil {

fmt.Println(err.Error())

respondWithError(w, http.StatusInternalServerError, err.Error())

return

}

respondWithJSON(w, http.StatusCreated, user)

} After the method responsible for creating a user, let's write the method responsible for editing a user. We will call this the updateUser method. In this method, we get the ID of the user that should be modified, translate the body of the request received in JSON for the instance, and then call the update method to modify the data instance. If there is no error, we will send the corresponding HTTP code:

func (a *App) updateUser(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

vars := mux.Vars(r)

id, err := strconv.Atoi(vars["id"])

if err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusBadRequest, "Invalid product ID")

return

}

var user User

decoder := json.NewDecoder(r.Body)

if err := decoder.Decode(&user); err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusBadRequest, "Invalid resquest payload")

return

}

defer r.Body.Close()

user.ID = id

if err := user.update(a.DB); err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusInternalServerError, err.Error())

return

}

respondWithJSON(w, http.StatusOK, user)

} Finally, let's write the last method of our CRUD, which is responsible for removing a user from the database. Let's call this method deleteUser. In this method, we get the id as a parameter and use this data to create an instance of the user. Once the instance is created, the delete method of the instance is called. If there are no errors, the corresponding HTTP code is sent:

func (a *App) deleteUser(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

vars := mux.Vars(r)

id, err := strconv.Atoi(vars["id"])

if err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusBadRequest, "Invalid User ID")

return

}

user := User{ID: id}

if err := user.delete(a.DB); err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusInternalServerError, err.Error())

return

}

respondWithJSON(w, http.StatusOK, map[string]string{"result": "success"})

} Finally, our app.go file looks as follows:

package main

import (

"database/sql"

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"log"

"net/http"

"strconv"

"github.com/codegangsta/negroni"

"github.com/gorilla/mux"

"github.com/jmoiron/sqlx"

_ "github.com/lib/pq"

)App is the struct with app configuration values:

type App struct {

DB *sqlx.DB

Router *mux.Router

} Initialize creates the DB connection and prepares all the routes:

func (a *App) Initialize(db *sqlx.DB) {

a.DB = db

a.Router = mux.NewRouter()

a.initializeRoutes()

} func (a *App) initializeRoutes() {

a.Router.HandleFunc("/users", a.getUsers).Methods("GET")

a.Router.HandleFunc("/user", a.createUser).Methods("POST")

a.Router.HandleFunc("/user/{id:[0-9]+}",

a.getUser).Methods("GET")

a.Router.HandleFunc("/user/{id:[0-9]+}",

a.updateUser).Methods("PUT")

a.Router.HandleFunc("/user/{id:[0-9]+}",

a.deleteUser).Methods("DELETE")

} Run initializes the server:

func (a *App) Run(addr string) {

n := negroni.Classic()

n.UseHandler(a.Router)

log.Fatal(http.ListenAndServe(addr, n))

}

func (a *App) getUser(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

vars := mux.Vars(r)

id, err := strconv.Atoi(vars["id"])

if err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusBadRequest, "Invalid product ID")

return

}

user := User{ID: id}

if err := user.get(a.DB); err != nil {

switch err {

case sql.ErrNoRows:

respondWithError(w, http.StatusNotFound, "User not found")

default:

respondWithError(w, http.StatusInternalServerError, err.Error())

}

return

}

respondWithJSON(w, http.StatusOK, user)

}

func (a *App) getUsers(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

count, _ := strconv.Atoi(r.FormValue("count"))

start, _ := strconv.Atoi(r.FormValue("start"))

if count > 10 || count < 1 {

count = 10

}

if start < 0 {

start = 0

}

users, err := list(a.DB, start, count)

if err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusInternalServerError, err.Error())

return

}

respondWithJSON(w, http.StatusOK, users)

}

func (a *App) createUser(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var user User

decoder := json.NewDecoder(r.Body)

if err := decoder.Decode(&user); err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusBadRequest, "Invalid request payload")

return

}

defer r.Body.Close()

if err := user.create(a.DB); err != nil {

fmt.Println(err.Error())

respondWithError(w, http.StatusInternalServerError, err.Error())

return

}

respondWithJSON(w, http.StatusCreated, user)

}

func (a *App) updateUser(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

vars := mux.Vars(r)

id, err := strconv.Atoi(vars["id"])

if err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusBadRequest, "Invalid product ID")

return

}

var user User

decoder := json.NewDecoder(r.Body)

if err := decoder.Decode(&user); err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusBadRequest, "Invalid resquest payload")

return

}

defer r.Body.Close()

user.ID = id

if err := user.update(a.DB); err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusInternalServerError, err.Error())

return

}

respondWithJSON(w, http.StatusOK, user)

}

func (a *App) deleteUser(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

vars := mux.Vars(r)

id, err := strconv.Atoi(vars["id"])

if err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusBadRequest, "Invalid User ID")

return

}

user := User{ID: id}

if err := user.delete(a.DB); err != nil {

respondWithError(w, http.StatusInternalServerError, err.Error())

return

}

respondWithJSON(w, http.StatusOK, map[string]string{"result": "success"})

}

func respondWithError(w http.ResponseWriter, code int, message string) {

respondWithJSON(w, code, map[string]string{"error": message})

}

func respondWithJSON(w http.ResponseWriter, code int,

payload interface{}) {

response, _ := json.Marshal(payload)

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json")

w.WriteHeader(code)

w.Write(response)

} The code may look big, but it's actually fairly concise within the concept of our microservice.

The main.go file

Now that you have a basic understanding of our project, let's take a look at the main.go file. This is the file responsible for sending settings necessary for the operation of our microservice to our app and for running the microservice itself. As can be seen in the following code, we instantiate a connection to the database from the beginning. This instance is the database that will be used in every application:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"github.com/jmoiron/sqlx"

_ "github.com/lib/pq"

"log"

"os"

)

func main() {

connectionString := fmt.Sprintf(

"user=%s password=%s dbname=%s sslmode=disable",

os.Getenv("APP_DB_USERNAME"),

os.Getenv("APP_DB_PASSWORD"),

os.Getenv("APP_DB_NAME"),

)

db, err := sqlx.Open("postgres", connectionString)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

a := App{}

a.Initialize(cache, db)

a.Run(":8080")

} Unlike the app.go file, main.go is leaner. In Go, the whole application is initialized by executing a function, main. In our microservice, it is no different. Our main method sends to the App instance what is necessary to connect the database. At the end of the Run method, it runs the application server on port 8080.