RL formalisms

Every scientific and engineering field has its own assumptions and limitations. In the previous section, we discussed supervised learning, in which such assumptions are the knowledge of input-output pairs. You have no labels for your data? You need to figure out how to obtain labels or try to use some other theory. This doesn't make supervised learning good or bad; it just makes it inapplicable to your problem.

There are many historical examples of practical and theoretical breakthroughs that have occurred when somebody tried to challenge rules in a creative way. However, we also must understand our limitations. It's important to know and understand game rules for various methods, as it can save you tons of time in advance. Of course, such formalisms exist for RL, and we will spend the rest of this book analyzing them from various angles.

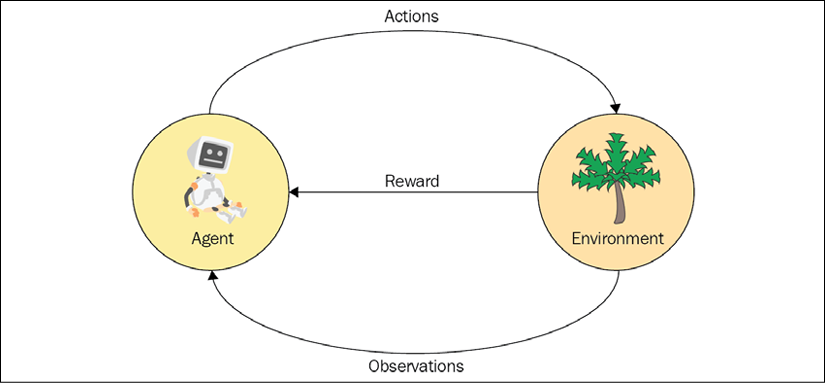

The following diagram shows two major RL entities—agent and environment—and their communication channels—actions, reward, and observations. We will discuss them in detail in the next few sections:

Figure 1.2: RL entities and their communication channels

Reward

Let's return to the notion of reward. In RL, it's just a scalar value we obtain periodically from the environment. As mentioned, reward can be positive or negative, large or small, but it's just a number. The purpose of reward is to tell our agent how well it has behaved. We don't define how frequently the agent receives this reward; it can be every second or once in an agent's lifetime, although it's common practice to receive rewards every fixed timestamp or at every environment interaction, just for convenience. In the case of once-in-a-lifetime reward systems, all rewards except the last one will be zero.

As I stated, the purpose of reward is to give an agent feedback about its success, and it's a central thing in RL. Basically, the term reinforcement comes from the fact that reward obtained by an agent should reinforce its behavior in a positive or negative way. Reward is local, meaning that it reflects the success of the agent's recent activity and not all the successes achieved by the agent so far. Of course, getting a large reward for some action doesn't mean that a second later you won't face dramatic consequences as a result of your previous decisions. It's like robbing a bank—it could look like a good idea until you think about the consequences.

What an agent is trying to achieve is the largest accumulated reward over its sequence of actions. To give you a better understanding of reward, here is a list of some concrete examples with their rewards:

- Financial trading: An amount of profit is a reward for a trader buying and selling stocks.

- Chess: Reward is obtained at the end of the game as a win, lose, or draw. Of course, it's up to interpretation. For me, for example, achieving a draw in a match against a chess grandmaster would be a huge reward. In practice, we need to specify the exact reward value, but it could be a fairly complicated expression. For instance, in the case of chess, the reward could be proportional to the opponent's strength.

- Dopamine system in the brain: There is a part of the brain (limbic system) that produces dopamine every time it needs to send a positive signal to the rest of the brain. Higher concentrations of dopamine lead to a sense of pleasure, which reinforces activities considered by this system to be good. Unfortunately, the limbic system is ancient in terms of the things it considers good—food, reproduction, and dominance—but that is a totally different story!

- Computer games: They usually give obvious feedback to the player, which is either the number of enemies killed or a score gathered. Note in this example that reward is already accumulated, so the RL reward for arcade games should be the derivative of the score, that is, +1 every time a new enemy is killed and 0 at all other time steps.

- Web navigation: There are problems, with high practical value, that require the automated extraction of information available on the web. Search engines are trying to solve this task in general, but sometimes, to get to the data you're looking for, you need to fill in some forms or navigate through a series of links, or complete CAPTCHAs, which can be difficult for search engines to do. There is an RL-based approach to those tasks in which the reward is the information or the outcome that you need to get.

- Neural network (NN) architecture search: RL has been successfully applied to the domain of NN architecture optimization, where the aim is to get the best performance metric on some dataset by tweaking the number of layers or their parameters, adding extra bypass connections, or making other changes to the NN architecture. The reward in this case is the performance (accuracy or another measure showing how accurate the NN predictions are).

- Dog training: If you have ever tried to train a dog, you know that you need to give it something tasty (but not too much) every time it does the thing you've asked. It's also common to punish your pet a bit (negative reward) when it doesn't follow your orders, although recent studies have shown that this isn't as effective as a positive reward.

- School marks: We all have experience here! School marks are a reward system designed to give pupils feedback about their studying.

As you can see from the preceding examples, the notion of reward is a very general indication of the agent's performance, and it can be found or artificially injected into lots of practical problems around us.

The agent

An agent is somebody or something who/that interacts with the environment by executing certain actions, making observations, and receiving eventual rewards for this. In most practical RL scenarios, the agent is our piece of software that is supposed to solve some problem in a more-or-less efficient way. For our initial set of six examples, the agents will be as follows:

- Financial trading: A trading system or a trader making decisions about order execution

- Chess: A player or a computer program

- Dopamine system: The brain itself, which, according to sensory data, decides whether it was a good experience

- Computer games: The player who enjoys the game or the computer program. (Andrej Karpathy once tweeted that "we were supposed to make AI do all the work and we play games but we do all the work and the AI is playing games!")

- Web navigation: The software that tells the browser which links to click on, where to move the mouse, or which text to enter

- NN architecture search: The software that controls the concrete architecture of the NN being evaluated

- Dog training: You make decisions about the actions (feeding/punishing), so, the agent is you

- School: Student/pupil

The environment

The environment is everything outside of an agent. In the most general sense, it's the rest of the universe, but this goes slightly overboard and exceeds the capacity of even tomorrow's computers, so we usually follow the general sense here.

The agent's communication with the environment is limited to reward (obtained from the environment), actions (executed by the agent and given to the environment), and observations (some information besides the reward that the agent receives from the environment). We have discussed reward already, so let's talk about actions and observations next.

Actions

Actions are things that an agent can do in the environment. Actions can, for example, be moves allowed by the rules of play (if it's a game), or doing homework (in the case of school). They can be as simple as move pawn one space forward or as complicated as fill the tax form in for tomorrow morning.

In RL, we distinguish between two types of actions—discrete or continuous. Discrete actions form the finite set of mutually exclusive things an agent can do, such as move left or right. Continuous actions have some value attached to them, such as a car's action turn the wheel having an angle and direction of steering. Different angles could lead to a different scenario a second later, so just turn the wheel is definitely not enough.

Observations

Observations of the environment form the second information channel for an agent, with the first being reward. You may be wondering why we need a separate data source. The answer is convenience. Observations are pieces of information that the environment provides the agent with that say what's going on around the agent.

Observations may be relevant to the upcoming reward (such as seeing a bank notification about being paid) or may not be. Observations can even include reward information in some vague or obfuscated form, such as score numbers on a computer game's screen. Score numbers are just pixels, but potentially we could convert them into reward values; it's not a big deal with modern DL at hand.

On the other hand, reward shouldn't be seen as a secondary or unimportant thing—reward is the main force that drives the agent's learning process. If a reward is wrong, noisy, or just slightly off course from the primary objective, then there is a chance that training will go in a wrong direction.

It's also important to distinguish between an environment's state and observations. The state of an environment potentially includes every atom in the universe, which makes it impossible to measure everything about the environment. Even if we limit the environment's state to be small enough, most of the time, it will be either not possible to get full information about it or our measurements will contain noise. This is completely fine, though, and RL was created to support such cases natively. Once again, let's return to our set of examples to capture the difference:

- Financial trading: Here, the environment is the whole financial market and everything that influences it. This is a huge list of things, such as the latest news, economic and political conditions, weather, food supplies, and Twitter trends. Even your decision to stay home today can potentially indirectly influence the world's financial system (if you believe in the "butterfly effect"). However, our observations are limited to stock prices, news, and so on. We don't have access to most of the environment's state, which makes trading such a nontrivial thing.

- Chess: The environment here is your board plus your opponent, which includes their chess skills, mood, brain state, chosen tactics, and so on. Observations are what you see (your current chess position), but, at some levels of play, knowledge of psychology and the ability to read an opponent's mood could increase your chances.

- Dopamine system: The environment here is your brain plus your nervous system and your organs' states plus the whole world you can perceive. Observations are the inner brain state and signals coming from your senses.

- Computer game: Here, the environment is your computer's state, including all memory and disk data. For networked games, you need to include other computers plus all Internet infrastructure between them and your machine. Observations are a screen's pixels and sound only. These pixels are not a tiny amount of information (somebody calculated that the total number of possible moderate-size images (1024×768) is significantly larger than the number of atoms in our galaxy), but the whole environment state is definitely larger.

- Web navigation: The environment here is the Internet, including all the network infrastructure between the computer on which our agent works and the web server, which is a really huge system that includes millions and millions of different components. The observation is normally the web page that is loaded at the current navigation step.

- NN architecture search: In this example, the environment is fairly simple and includes the NN toolkit that performs the particular NN evaluation and the dataset that is used to obtain the performance metric. In comparison to the Internet, this looks like a tiny toy environment.

Observations might be different and include some information about testing, such as loss convergence dynamics or other metrics obtained from the evaluation step.

- Dog training: Here, the environment is your dog (including its hardly observable inner reactions, mood, and life experiences) and everything around it, including other dogs and even a cat hiding in a bush. Observations are signals from your senses and memory.

- School: The environment here is the school itself, the education system of the country, society, and the cultural legacy. Observations are the same as for the dog training example—the student's senses and memory.

This is our mise en scène and we will play around with it in the rest of this book. You will have already noticed that the RL model is extremely flexible and general, and it can be applied to a variety of scenarios. Let's now look at how RL is related to other disciplines, before diving into the details of the RL model.

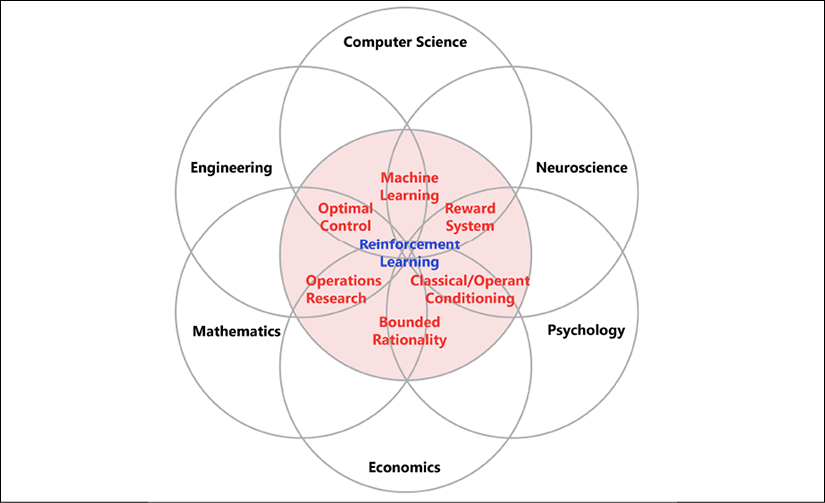

There are many other areas that contribute or relate to RL. The most significant are shown in the following diagram, which includes six large domains heavily overlapping each other on the methods and specific topics related to decision-making (shown inside the inner gray circle).

Figure 1.3: Various domains in RL

At the intersection of all those related, but still different, scientific areas sits RL, which is so general and flexible that it can take the best available information from these varying domains:

- ML: RL, being a subfield of ML, borrows lots of its machinery, tricks, and techniques from ML. Basically, the goal of RL is to learn how an agent should behave when it is given imperfect observational data.

- Engineering (especially optimal control): This helps with taking a sequence of optimal actions to get the best result.

- Neuroscience: We used the dopamine system as our example, and it has been shown that the human brain acts similarly to the RL model.

- Psychology: This studies behavior in various conditions, such as how people react and adapt, which is close to the RL topic.

- Economics: One of the important topics is how to maximize reward in terms of imperfect knowledge and the changing conditions of the real world.

- Mathematics: This works with idealized systems and also devotes significant attention to finding and reaching the optimal conditions in the field of operations research.

In the next part of the chapter, you will become familiar with the theoretical foundations of RL, which will make it possible to start moving toward the methods used to solve the RL problem. The upcoming section is important for understanding the rest of the book.