C++ compared with other languages

A multitude of application types, platforms, and programming languages have emerged since C++ was first released. Still, C++ remains a widely used language, and its compilers are available for most platforms. The major exception, as of today, is the web platform, where JavaScript and its related technologies are the foundation. However, the web platform is evolving into being able to execute what was previously only possible in desktop applications, and in that context, C++ has found its way into web applications using technologies such as Emscripten, asm.js, and WebAssembly.

In this section, we'll begin by looking at competing languages in the context of performance. Following this, we'll look at how C++ handles object ownership and garbage collection in comparison to other languages, and how we can avoid null objects in C++. Finally, we'll cover some drawbacks of C++ that users should keep in mind when considering whether the language is appropriate for their requirements.

Competing languages and performance

In order to understand how C++ achieves its performance compared to other programming languages, let's discuss some fundamental differences between C++ and most other modern programming languages.

For simplicity, this section will focus on comparing C++ to Java, although the comparisons for most parts also apply to other programming language based upon a garbage collector, such as C# and JavaScript.

Firstly, Java compiles to bytecode, which is then compiled to machine code while the application is executing, whereas the majority of C++ implementations directly compiles the source code to machine code. Although bytecode and just-in-time compilers may theoretically be able to achieve the same (or, theoretically, even better) performance than precompiled machine code, as of today, they usually do not. To be fair, though, they perform well enough for most cases.

Secondly, Java handles dynamic memory in a completely different manner from C++. In Java, memory is automatically deallocated by a garbage collector, whereas a C++ program handles memory deallocations manually or by a reference counting mechanism. The garbage collector does prevent memory leaks, but at the cost of performance and predictability.

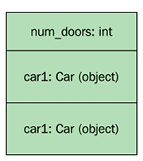

Thirdly, Java places all its objects in separate heap allocations, whereas C++ allows the programmer to place objects both on the stack and on the heap. In C++, it's also possible to create multiple objects in one single heap allocation. This can be a huge performance gain for two reasons: objects can be created without always allocating dynamic memory, and multiple related objects can be placed adjacent to one another in memory.

Take a look at how memory is allocated in the following example. The C++ function uses the stack for both objects and integers; Java places the objects on the heap:

|

C++ |

Java |

|

|

|

C++ places everything on the stack:  |

Java places the  |

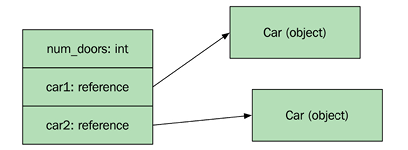

Now take a look at the next example and see how an array of Car objects are placed in memory when using C++ and Java, respectively:

|

C++ |

Java |

|

|

|

The following diagram shows how the  |

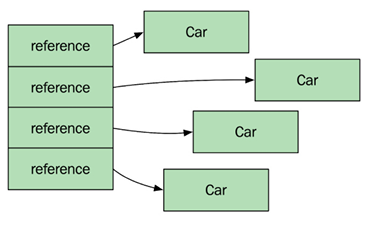

The following diagram shows how the  |

The C++ vector contains the actual Car objects placed in one contiguous memory block, whereas the equivalent in Java is a contiguous memory block of references to Car objects. In Java, the objects have been allocated separately, which means that they can be located anywhere on the heap.

This affects the performance, as Java, in this example, effectively has to execute five allocations in the Java heap space. It also means that whenever the application iterates the list, there is a performance win for C++, since accessing nearby memory locations is faster than accessing several random spots in memory.

Non-performance-related C++ language features

It's tempting to believe that C++ should only be used if performance is a major concern. Isn't it the case that C++ just increases the complexity of the code base due to manual memory handling, which may result in memory leaks and hard-to-track bugs?

This may have been true several C++ versions ago, but a modern C++ programmer relies on the provided containers and smart pointer types, which are part of the standard library. A substantial part of the C++ features added over the last 10 years has made the language both more powerful and simpler to use.

I would like to highlight some old but powerful features of C++ here that relate to robustness rather than performance, which are easily overlooked: value semantics, const correctness, ownership, deterministic destruction, and references.

Value semantics

C++ supports both value semantics and reference semantics. Value semantics lets us pass objects by value instead of just passing references to objects. In C++, value semantics is the default, which means that when you pass an instance of a class or struct, it behaves in the same way as passing an int, float, or any other fundamental type. To use reference semantics, we need to explicitly use references or pointers.

The C++ type system gives us the ability to explicitly state the ownership of an object. Compare the following implementations of a simple class in C++ and Java. We will start with the C++ version:

// C++

class Bagel {

public:

Bagel(std::set<std::string> ts) : toppings_(std::move(ts)) {}

private:

std::set<std::string> toppings_;

};

The corresponding implementation in Java could look like this:

// Java

class Bagel {

public Bagel(ArrayList<String> ts) { toppings_ = ts; }

private ArrayList<String> toppings_;

}

In the C++ version, the programmer states that the toppings are completely encapsulated by the Bagel class. Had the programmer intended the topping list to be shared among several bagels, it would have been declared as a pointer of some kind: std::shared_ptr if the ownership is shared among several bagels, or std::weak_ptr if someone else owns the topping list and is supposed to modify it as the program executes.

In Java, objects reference each other with shared ownership. Therefore, it's not possible to distinguish whether the topping list is intended to be shared among several bagels or not, or whether it is handled somewhere else or, if it is, as in most cases, completely owned by the Bagel class.

Compare the following functions; as every object is shared by default in Java (and most other languages), programmers have to take precautions for subtle bugs such as this:

|

C++ |

Java |

|

|

Const correctness

Another powerful feature of C++, which Java and many other languages lack, is the ability to write fully const correct code. Const correctness means that each member function signature of a class explicitly tells the caller whether the object will be modified or not; and it will not compile if the caller tries to modify an object declared const. In Java, it is possible to declare constants using the final keyword, but this lacks the ability to declare member functions as const.

Here is an example of how we can use const member functions to prevent unintentional modifications of objects. In the following Person class, the member function age() is declared const and is therefore not allowed to mutate the Person object, whereas set_age() mutates the object and cannot be declared const:

class Person {

public:

auto age() const { return age_; }

auto set_age(int age) { age_ = age; }

private:

int age_{};

};

It's also possible to distinguish between returning mutable and immutable references to members. In the following Team class, the member function leader() const returns an immutable Person, whereas leader() returns a Person object that may be mutated:

class Team {

public:

auto& leader() const { return leader_; }

auto& leader() { return leader_; }

private:

Person leader_{};

};

Now let's see how the compiler can help us find errors when we try to mutate immutable objects. In the following example, the function argument teams is declared const, explicitly showing that this function is not allowed to modify them:

void nonmutating_func(const std::vector<Team>& teams) {

auto tot_age = 0;

// Compiles, both leader() and age() are declared const

for (const auto& team : teams)

tot_age += team.leader().age();

// Will not compile, set_age() requires a mutable object

for (auto& team : teams)

team.leader().set_age(20);

}

If we want to write a function that can mutate the teams object, we simply remove const. This signals to the caller that this function may mutate the teams:

void mutating_func(std::vector<Team>& teams) {

auto tot_age = 0;

// Compiles, const functions can be called on mutable objects

for (const auto& team : teams)

tot_age += team.leader().age();

// Compiles, teams is a mutable variable

for (auto& team : teams)

team.leader().set_age(20);

}

Object ownership

Except in very rare situations, a C++ programmer should leave the memory handling to containers and smart pointers, and never have to rely on manual memory handling.

To put it clearly, the garbage collection model in Java could almost be emulated in C++ by using std::shared_ptr for every object. Note that garbage-collecting languages don't use the same algorithm for allocation tracking as std::shared_ptr. The std::shared_ptr is a smart pointer based on a reference-counting algorithm that will leak memory if objects have cyclic dependencies. Garbage-collecting languages have more sophisticated methods that can handle and free cyclic dependent objects.

However, rather than relying on a garbage collector, forcing a strict ownership delicately avoids subtle bugs that may result from sharing objects by default, as in the case of Java.

If a programmer minimizes shared ownership in C++, the resulting code is easier to use and harder to abuse, as it can force the user of the class to use it as it is intended.

Deterministic destruction in C++

The destruction of objects is deterministic in C++. That means that we (can) know exactly when an object is being destroyed. This is not the case for garbage-collected languages like Java where the garbage collector decides when an unreferenced object is being finalized.

In C++, we can reliably reverse what has been done during the lifetime of an object. At first, this might seem like a small thing. But it turns out to have a great impact on how we can provide exception safety guarantees and handle resources (such as memory, file handles, mutex locks, and more) in C++.

Deterministic destruction is also one of the features that makes C++ predictable. Something that is highly valued among programmers and a requirement for performance-critical applications.

We will spend more time talking about object ownership, lifetimes, and resource management later on in the book. So don't be too worried if this doesn't make much sense at the moment.

Avoiding null objects using C++ references

In addition to strict ownership, C++ also has the concept of references, which is different from references in Java. Internally, a reference is a pointer that is not allowed to be null or repointed; therefore, no copying is involved when passing it to a function.

As a result, a function signature in C++ can explicitly restrict the programmer from passing a null object as a parameter. In Java, the programmer must use documentation or annotations to indicate non-null parameters.

Take a look at these two Java functions for computing the volume of a sphere. The first one throws a runtime exception if a null object is passed to it, whereas the second one silently ignores null objects.

This first implementation in Java throws a runtime exception if passed a null object:

// Java

float getVolume1(Sphere s) {

float cube = Math.pow(s.radius(), 3);

return (Math.PI * 4 / 3) * cube;

}

This second implementation in Java silently handles null objects:

// Java

float getVolume2(Sphere s) {

float rad = s == null ? 0.0f : s.radius();

float cube = Math.pow(rad, 3);

return (Math.PI * 4 / 3) * cube;

}

In both functions implemented in Java, the caller of the function has to inspect the implementation of the function in order to determine whether null objects are allowed or not.

In C++, the first function signature explicitly accepts only initialized objects by using a reference that cannot be null. The second version using a pointer as an argument explicitly shows that null objects are handled.

C++ arguments passed as references indicates that null values are not allowed:

auto get_volume1(const Sphere& s) {

auto cube = std::pow(s.radius(), 3.f);

auto pi = 3.14f;

return (pi * 4.f / 3.f) * cube;

}

C++ arguments passed as pointers indicates that null values are being handled:

auto get_volume2(const Sphere* s) {

auto rad = s ? s->radius() : 0.f;

auto cube = std::pow(rad, 3);

auto pi = 3.14f;

return (pi * 4.f / 3.f) * cube;

}

Being able to use references or values as arguments in C++ instantly informs the C++ programmer how the function is intended to be used. Conversely, in Java, the user must inspect the implementation of the function, as objects are always passed as pointers, and there's a possibility that they could be null.

Drawbacks of C++

Comparing C++ with other programming languages wouldn't be fair without mentioning some of its drawbacks. As mentioned earlier, C++ has more concepts to learn, and is therefore harder to use correctly and to its full potential. However, if a programmer can master C++, the higher complexity turns into an advantage and the code base becomes more robust and performs better.

There are, nonetheless, some shortcomings of C++, which are simply just shortcomings. The most severe of those shortcomings are long compilation times and the complexity of importing libraries. Up until C++20, C++ has relied on an outdated import system where imported headers are simply pasted into whatever includes them. C++ modules, which are being introduced in C++20, will solve some of the problems of the system, which is based on including header files, and will also have a positive impact on compilation times for large projects.

Another apparent drawback of C++ is the lack of provided libraries. While other languages usually come with all the libraries needed for most applications, such as graphics, user interfaces, networking, threading, resource handling, and so on, C++ provides, more or less, nothing more than the bare minimum of algorithms, threads, and, as of C++17, file system handling. For everything else, programmers have to rely on external libraries.

To summarize, although C++ has a steeper learning curve than most other languages, if used correctly, the robustness of C++ is an advantage compared to many other languages. So, despite the compilation times and lack of provided libraries, I believe that C++ is a well-suited language for large-scale projects, even for projects where performance is not the highest priority.