Getting started with AWK

This section describes how to set up the AWK environment on your GNU/Linux system, and we'll also discuss the workflow of AWK. Then, we'll look at different methods for executing AWK programs.

Installation on Linux

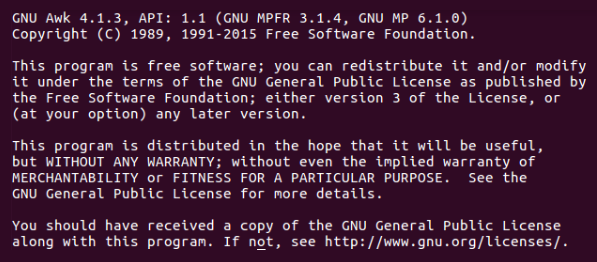

All the examples in this book are covered using Linux distribution (openSUSE Leap 42.3). In order to practice examples discussed in this book, you need GNU AWK version 4.1.3 or above to be installed on your systems. Although there won't be drastic changes if you use earlier versions, we still recommend you use the same version to get along.

Generally, AWK is installed by default on most GNU/Linux distributions. Using the which command, you can check whether it is installed on your system or not. In case AWK is not installed on your system, you can do so in one of two ways:

- Using the package manager of the corresponding GNU/Linux system

- Compiling from the source code

Let's take a look at each method in detail in the following sections.

Using the package manager

Different flavors of GNU/Linux distribution have different package-management utilities. If you are using a Debian-based GNU/Linux distribution, such as Ubuntu, Mint, or Debian, then you can install it using the Advance Package Tool (APT) package manager, as follows:

[ shiwang@linux ~ ] $ sudo apt-get update -y [ shiwang@linux ~ ] $ sudo apt-get install gawk -y

Similarly, to install AWK on an RPM-based GNU/Linux distribution, such as Fedora, CentOS, or RHEL, you can use the Yellowdog Updator Modified (YUM) package manager, as follows:

[ root@linux ~ ] # yum update -y [ root@linux ~ ] # yum install gawk -y

For installation of AWK on openSUSE, you can use the zypper (zypper command line) package-management utility, as follows:

[ root@linux ~ ] # zypper update -y [ root@linux ~ ] # zypper install gawk -y

Once installation is finished, make sure AWK is accessible through the command line. We can check that using the which command, which will return the absolute path of AWK on our system:

[ root@linux ~ ] # which awk /usr/bin/awk

You can also use awk --versionto find the AWK version on our system:

[ root@linux ~ ] # awk --version

Compiling from the source code

Like every other open source utility, the GNU AWK source code is freely available for download as part of the GNU project. Previously, you saw how to install AWK using the package manager; now, you will see how to install AWK by compiling from its source code on the GNU/Linux distribution. The following steps are applicable to most of the GNU/Linux software for installation:

- Download the source code from a GNU project ftp site. Here, we will use the

wgetcommand line utility to download it, however you are free to choose any other program, such ascurl, you feel comfortable with:

[ shiwang@linux ~ ] $ wget http://ftp.gnu.org/gnu/gawk/gawk-4.1.3.tar.xz- Extract the downloaded source code:

[ shiwang@linux ~ ] $ tar xvf gawk-4.1.3.tar.xz- Change your working directory and execute the

configurefile to configure the GAWK as per the working environment of your system:

[ shiwang@linux ~ ] $ cd gawk-4.1.3 && ./configure- Once the

configurecommand completes its execution successfully, it will generate themakefile. Now, compile the source code by executing themakecommand:

[ shiwang@linux ~ ] $ make- Type

make installto install the programs and any data files and documentation. When installing into a prefix owned by root, it is recommended that the package be configured and built as a regular user, and only themake installphase is executed with root privileges:

[ shiwang@linux ~ ] $ sudo make install- Upon successful execution of these five steps, you have compiled and installed AWK on your GNU/Linux distribution. You can verify this by executing the

which awkcommand in the Terminal orawk --version:

[ root@linux ~ ] # which awk /usr/bin/awk

Now you have a working AWK/GAWK installation and we are ready to begin AWK programming, but before that, our next section describes the workflow of the AWK interpreter.

Note

If you are running on macOS X, AWK, and not GAWK, would be installed as a default on it. For GAWK installation on macOS X, please refer to MacPorts for GAWK.

Workflow of AWK

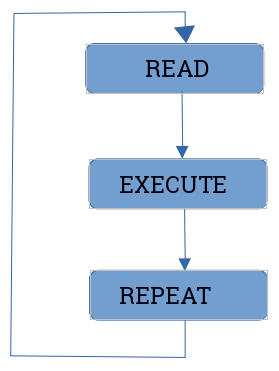

Having a basic knowledge of the AWK interpreter workflow will help you to better understand AWK and will result in more efficient AWK program development. Hence, before getting your hands dirty with AWK programming, you need to understand its internals. The AWK workflow can be summarized as shown in the following figure:

Figure 1.1: AWK workflow

Let's take a look at each operation:

- READ OPERATION: AWK reads a line from the input stream (file, pipe, or stdin) and stores it in memory. It works on text input, which can be a file, the standard input stream, or from a pipe, which it further splits into records and fields:

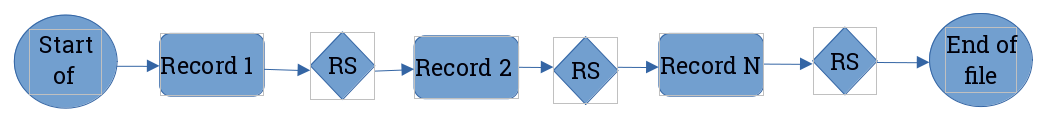

- Records: An AWK record is a single, continuous data input that AWK works on. Records are bounded by a record separator, whose value is stored in the RS variable. The default value of RS is set to a newline character. So, the lines of input are considered records for the AWK interpreter. Records are read continuously until the end of the input is reached. Figure 1.2 shows how input data is broken into records and then goes further into how it is split into fields:

Figure 1.2: AWK input data is split into records with the record separator

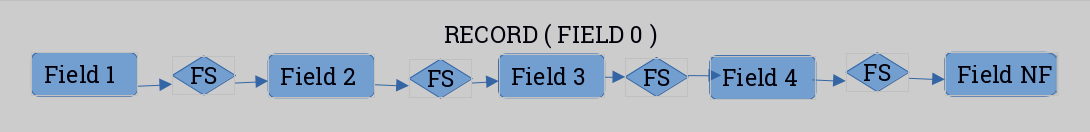

- Fields: Each record can further be broken down into individual chunks called fields. Like records, fields are bounded. The default field separator is any amount of whitespace, including tab and space characters. So by default, lines of input are further broken down into individual words separated by whitespace. You can refer to the fields of a record by a field number, beginning with 1. The last field in each record can be accessed by its number or with the

NFspecial variable, which contains the number of fields in the current record, as shown in Figure 1.3:

- Fields: Each record can further be broken down into individual chunks called fields. Like records, fields are bounded. The default field separator is any amount of whitespace, including tab and space characters. So by default, lines of input are further broken down into individual words separated by whitespace. You can refer to the fields of a record by a field number, beginning with 1. The last field in each record can be accessed by its number or with the

Figure 1.3: Records are split into fields by a field separator

- EXECUTE OPERATION: All AWK commands are applied sequentially on the input (records and fields). By default, AWK executes commands on each record/line. This behavior of AWK can be restricted by the use of patterns.

- REPEAT OPERATION: The process of read and execute is repeated until the end of the file is reached.

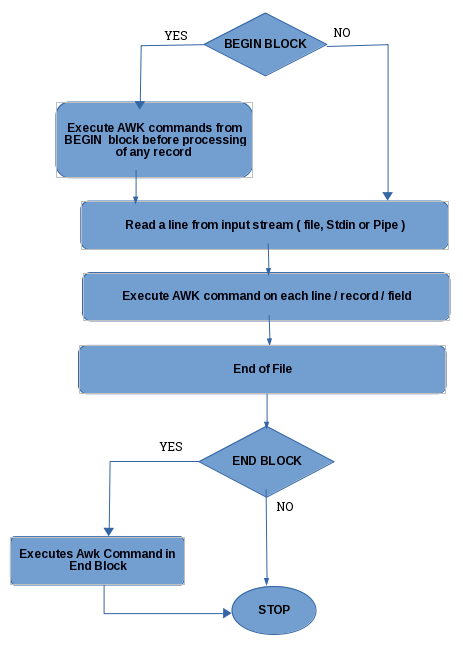

The following flowchart depicts the workflow of the AWK interpreter:

Figure 1.4: Workflow of the AWK interpreter

Action and pattern structure of AWK

AWK programs are sequences of one or more patterns followed by action statements. These action-pattern statements are separated by newlines. Both actions (AWK commands) and patterns (search patterns) are optional, hence we use { } to distinguish them:

/ search pattern / { action / awk-commands }/ search pattern / { action / awk-commands }

AWK reads each input line one after the other, and searches for matches of the given pattern. If the current input line matches the given pattern, a corresponding action is taken. Then, the next input line is read and the matching of patterns starts again. This process continues until all input is read.

Note

Throughout this book, we will be using the terms patterns or search patterns and actions or AWK commands interchangeably.

In AWK syntax, we can omit either patterns or actions (but not both) in a single pattern-action statement. Where a search pattern has no action statement (AWK command), each line for which a pattern matches is printed to the output.

Note

Each action statement can be single or multiple AWK commands.

Multiple AWK commands on a single line are seperated by a semicolon (;).

A semicolon can be put at the end of any statement.

Example data file

Before proceeding, let's create a empinfo.txt file for practice. Each line in the file contains the name of the employee, their phone number, email address, job profile, salary in USD, and working days in a week:

Jack 9857532312 [email protected] hr 2000 5 Jane 9837432312 [email protected] hr 1800 5 Eva 8827232115 [email protected] lgs 2100 6 amit 9911887766 [email protected] lgs 2350 6 Julie 8826234556 [email protected] hr 2500 5

Pattern-only statements

The syntax of the awk command with a pattern only is as follows:

awk '/ pattern /' inputfilename

In the given example, all lines of the empinfo.txt file are processed, and those that contain the Jane pattern are printed:

$ awk '/Jane/' empinfo.txt Jane 9837432312 [email protected] hr 1800 5

Action-only statements

The syntax of the awk command with an action only is as follows:

awk '{ action statements / awk-commands }' inputfilenames

If you omit the pattern and give the action statement (AWK commands), then the given action is performed on all input lines, for example:

$ awk '{ print $1 }' empinfo.txt Jack Jane Eva amit Julie

In the given example, all employee names are printed on the screen as $1, representing the first field of each input line.

Note

An empty pattern, that is / /, matches the null character and is equivalent to giving no pattern at all. If we specify an empty pattern, it will print each input record of the input file. An empty action, that is { }, specifies that doing nothing will not print any input record of the input file.

Printing each input line/record

We can print each input record of the input file in multiple ways, as shown in the following example. All the given examples will produce the same result by printing all the input records of the input file.

In our first example, we specify the empty pattern without any action statement to print each input record of the input file, as follows:

$ awk '//' empinfo.txtIn this example, we specify the print action statement only, without giving any pattern for matching, and print each input record of the input file, as follows:

$ awk '{ print }' empinfo.txtIn this example, we specify the $0 default variable, along with the print action statement, to print each input record of the input file, as follows:

$ awk '{ print $0 }' empinfo.txtIn this example, we specify the empty expression along with the print action statement to print each input record of the input file, as follows:

$ awk '//{ print }' empinfo.txtAll of the given examples perform the basic printing operation using AWK. On execution of any of the preceding examples, we will get the following output:

Jack 9857532312 [email protected] hr 2000 5 Jane 9837432312 [email protected] hr 1800 5 Eva 8827232115 [email protected] lgs 2100 6 amit 9911887766 [email protected] lgs 2350 6 Julie 8826234556 [email protected] hr 2500 5

Using the BEGIN and END blocks construct

AWK contains two special keywords, BEGIN and END, for patterns where an action is required. Both of them are optional and are used without slashes. They don't match any input lines.

The BEGIN block

The BEGIN block is executed in the beginning, before the first input line of the first input file is read. This block is executed once only when the AWK program is started. It is frequently used to initialize the variables or to change the value of the AWK built-in variables, such as FS. The syntax of the BEGIN block is as follows:

BEGIN { action / awk-commands }

The body block

It is the same pattern-action block that we discussed at the beginning of the chapter. The syntax of the body block is as follows:

/ search pattern / { action / awk-commands }

In the body block, AWK commands are applied by default on each input line, however, we can restrict this behavior with the help of patterns. There are no keywords for the body block.

The END block

The END block is executed after the last input line of the last input file is read. This block is executed at the end and is generally used for rendering totals, averages, and for processing data and figures that were read in the various input records. The syntax of the END block is as follows:

END { action / awk-commands }

Note

We can have multiple BEGIN or END blocks in a program. The action in that block will get executed as per the appearance of the block in that program. It is not mandatory to have BEGIN first and END last. The BEGIN and END blocks do not contain patterns, they contain action statements only.

Here is an example of the usage of the BEGIN and END blocks:

$ awk 'BEGIN { print "==Employee Info==" } # begin block { print } # body block END { print "==ends here==" }' empinfo.txt # end block

On executing the code, we get the following result:

==Employee Info== Jack 9857532312 [email protected] hr 2000 5 Jane 9837432312 [email protected] hr 1800 5 Eva 8827232115 [email protected] lgs 2100 6 amit 9911887766 [email protected] lgs 2350 6 Julie 8826234556 [email protected] hr 2500 5 ===ends here==

Patterns

In pattern-action statements, the pattern is something that determines when an action is to be executed. We can summarize the usage of patterns as follows:

- BEGIN { statements }: The statements are executed once before any input has been read.

- END { statements }: The statements are executed once after all input has been read.

- expression { statements }: The statements are executed at each input line where the expression is true, that is, non-zero or non-null.

- / regular expression / { statements }: The statements are executed at each input line that contains a string matched by the regular expression.

- compound pattern { statements }: A compound pattern combines expressions with

&&(AND),||(OR),!(NOT), and parentheses; the statements are executed at each input line where the compound pattern is true. - pattern 1, pattern 2 { statements }: A range pattern matches each input line from a line matched by pattern 1 to the next line matched by pattern 2, inclusive; the statements are executed at each matching line. Here, the pattern range could be of regular expressions or addresses.

BEGIN and END do not combine with other patterns. A range pattern cannot be part of any other pattern. BEGIN and END are the only patterns that require an action.

Actions

In pattern-action statements, actions are single or multiple statements that are separated by a newline or semicolon. The statements in actions can include the following:

- Expression statements: These are made up of constants, variables, operators, and function calls. For example, x = x+ 2 is an assignment expression.

- Printing statements: These are print statements made with either

printorprintf. For example,print "Welcome to awk programming ". - Control-flow statements: These consist of various decision-making statements made with

if...elseand looping statements made with thewhile,for, anddoconstructs. Apart from these,break,continue,next, andexitare used for controlling the loop iterations. These are similar to C programming control-flow constructs. - { statements }: This format is used for grouping a block of different statements.

We will study these different types of action and pattern statements in detail in future chapters.

Running AWK programs

There are different ways to run an AWK program. For a short program, we can directly execute AWK commands on the Terminal, and for long AWK programs, we generally create an AWK program script or source file. In this section, we will discuss different methods of executing AWK programs.

AWK as a Unix command line

This is the most-used method of running AWK programs. In this method program, AWK commands are given in single quotes as the first argument of the AWK command line, as follows:

$ awk 'program' input file1 file2 file3 .......fileNHere, program refers to the sequence of pattern-action statements discussed earlier. In this format, the AWK interpreter is invoked from the shell or Terminal to process the input line of files. The quotes around program instruct the shell not to interpret the AWK character as a special shell character and treat the entire argument as singular, for the AWK program not for the shell. It also enables the program to continue on more than one line.

The format used to call the AWK program from inside of a shell script is the same one we used on the Unix/Linux command line. For example:

$ awk '{ print }' empinfo.txt /etc/passwd The preceding command will print every line of the empinfo.txt file, followed by the lines of the /etc/passwd file on your system, as follows:

Jack 9857532312 [email protected] hr 2000 5 Jane 9837432312 [email protected] hr 1800 5 Eva 8827232115 [email protected] lgs 2100 6 amit 9911887766 [email protected] lgs 2350 6 Julie 8826234556 [email protected] hr 2500 5 at:x:25:25:Batch jobs daemon:/var/spool/atjobs:/bin/bash avahi:x:481:480:User for Avahi:/run/avahi-daemon:/bin/false avahi-autoipd:x:493:493:User for Avahi IPv4LL:/var/lib/avahi-autoipd:/bin/false bin:x:1:1:bin:/bin:/bin/bash daemon:x:2:2:Daemon:/sbin:/bin/bash games:x:12:100:Games account:/var/games:/bin/bash man:x:13:62:Manual pages viewer:/var/cache/man:/bin/bash messagebus:x:499:499:User for D-Bus:/run/dbus:/bin/false ...................... ...................... till last line in /etc/passwd

AWK as a filter (reading input from the Terminal)

Filter commands can take their input from stdin instead of reading it from the file. We can omit giving input filenames at the command line while executing the awk program, and simply call it from the Terminal as:

$ awk 'program'In the previous example, AWK applies the program to whatever you type on the standard input, that is, the Terminal, until you type end-of-file by pressing Ctrl + D, for example:

$ awk '$2==50{ print }' apple 50 apple 50 banana 60 litchi 50 litchi 50 mango 55 grapes 40 pineapple 60 ........

The line that contains 50 in the second field is printed, hence it's repeated twice on the Terminal. This functionality of AWK can be used to experiment with AWK; all you need is to type your AWK commands first, then type data, and see what happens next. The only thing you have to take care of here is to enclose your AWK commands in single quotes on the command line. This prevents the shell expansion of special characters, such as $, and also allows your program to be longer than one line.

Here is one more example in which we take input from the pipe and process it with the AWK command:

$ echo -e "jack \nsam \ntarly \njerry" | awk '/sam/{ print }' On executing this code, you get the following result:

samWe will be using examples of executing the AWK command line on the Terminal throughout the book for explaining various topics. This type of operation is performed when the program (AWK commands) is short (up to a few lines).

Running AWK programs from the source file

When AWK programs are long, it is more convenient to put them in a separate file. Putting AWK programs in a file reduces errors and retyping. Its syntax is as follows:

$ awk -f source_file inputfile1 inputfile2 ............inputfileNThe -f option tells the AWK utility to read the AWK commands from source_file. Any filename can be used in place of source_file. For example, we can create a cmd.awk text file containing the AWK commands, as follows:

$ vi cmd.awk BEGIN { print "***Emp Info***" } { print }

Now, we instruct AWK to read the commands from the cmd.awk file and perform the given actions:

$ awk -f cmd.awk empinfo.txtOn executing the preceding command, we get the following result:

***Emp Info*** Jack 9857532312 [email protected] hr 2000 5 Jane 9837432312 [email protected] hr 1800 5 Eva 8827232115 [email protected] lgs 2100 6 amit 9911887766 [email protected] lgs 2350 6 Julie 8826234556 [email protected] hr 2500 5

It does the same thing as this:

$ awk 'BEGIN { print "***Emp Info***" } { print }' empinfo.txtNote

We don't usually need to put the filename specified with -f in single quotes, because filenames generally don't contain any shell special characters. In the cmd.awk source file, we didn't put the AWK commands in single quotes. The quotes are only needed when we execute the AWK command from the command line. We added the .awk extension in the filename to clearly identify the AWK program file; it doesn't affect the execution of the AWK program and hence is not mandatory.

AWK programs as executable script files

We can write self-contained AWK scripts to execute AWK commands, like we have with shell scripts to execute shell commands. We create the AWK script by using #!, followed by the absolute path of the AWK interpreter and the -f optional argument. The line beginning with #! tells the operating system to run the immediately-followed interpreter with the given argument and the full argument list of the executed program. For example, we can update the cmd.awk file to emp.awk, as follows:

$ vi emp.awk #!/usr/bin/awk -f BEGIN { print "***Emp Info***" } { print }

Give this file executable permissions (with the chmod utility), then simply run ./emp.awk empinfo.txt at the shell and the system will run AWK as if you had typed awk -f cmd.awk empinfo.txt:

$ chmod +x emp.awk $./emp.awk empinfo.txt ***Emp Info*** Jack 9857532312 [email protected] hr 2000 5 Jane 9837432312 [email protected] hr 1800 5 Eva 8827232115 [email protected] lgs 2100 6 amit 9911887766 [email protected] lgs 2350 6 Julie 8826234556 [email protected] hr 2500 5

Self-contained executable AWK scripts are useful when you want to write AWK programs that users can invoke without having to know it was written in AWK.

Extending the AWK command line on multiple lines

For short AWK programs, it is most convenient to execute them on the command line. This is done by enclosing AWK commands in single quotes. Yet at times, the AWK commands that you want to execute on the command line are longer than one line. In these situations, you can extend the AWK commands to multiple lines using \ as the last element on each line. It is also mandatory at that time to enclose AWK commands in single quotes. For example:

$ awk 'BEGIN { print "***Emp Info***" } \ > { print } \ > END { print "***Ends Here***" } ' empinfo.txt

It is the same as if we have executed the AWK command on a single line, as follows:

$ awk 'BEGIN { print "***Emp Info***" } { print } END{ print "***Ends Here***" }' empinfo.txtThe output of the previous executed AWK command is:

***Emp Info*** Jack 9857532312 [email protected] hr 2000 5 Jane 9837432312 [email protected] hr 1800 5 Eva 8827232115 [email protected] lgs 2100 6 amit 9911887766 [email protected] lgs 2350 6 Julie 8826234556 [email protected] hr 2500 5 ***Ends Here***

Comments in AWK

A comment is some text that is included in a program for documentation or human information. It is not an executable part of the program. It explains what a program does and how it does it. Almost every programming language has comments, as they make the program construct understandable.

In the AWK programming language, a comment begins with the hash symbol (#) and continues till the end of the line. It is not mandatory to have # as the first character on the line to mark it as a comment. Anything written after # is ignored by the AWK commands. For example, we can put the following in emp.awk and update it as emp_comment.awk:

$ vi emp_comment.awk #!/usr/bin/awk -f # Info : This program displays the employees information # Date : 09 Sept 2017 # Version : 1.0 # Author : Shiwang # Header part is defined in BEGIN block to display Company information BEGIN { print "****Employee Information of HMT Corp.****" } # Body Block comment { print } # End Block comment END { print "***Information Database ends here****" }

Now, give this program executable permission (using chmod) and execute it as follows:

$ ./emp_comment.awk empinfo.txtHere is the output:

****Employee Information of HMT Corp.**** Jack 9857532312 [email protected] hr 2000 5 Jane 9837432312 [email protected] hr 1800 5 Eva 8827232115 [email protected] lgs 2100 6 amit 9911887766 [email protected] lgs 2350 6 Julie 8826234556 [email protected] hr 2500 5 ***Information Database ends here****

Shell quotes with AWK

As you have seen, we will be using the command line for most of our short AWK programs. The best way to use it is by enclosing the entire program in single quotes, as follows:

$ awk '/ search pattern / { awk commands }' inputfile1 inputfile2When you are working on a shell, it is good to have a basic understanding of shell quoting rules. The following rules apply only to the POSIX-compliant, GNU Bourne Again Shell:

- Quoted and non-quoted items can be concatenated together. The same is true for quoted and non-quoted item concatenation. For example:

$ echo "Welcome to " Learning "awk" >>> Welcome to Learning awk

- If you precede any character with a backslash (

\) in double quotes, the shell removes the backslash on execution and treats subsequent characters as literal without having any special meaning:

$ echo "Apple are \$10 a dozen" >>> Apple are $10 a dozen

- Single quotes prevent shell expansions of the command and variable. Anything between the opening and closing quotes is not interpreted by the shell, it is passed as such to the command with which it is used:

$ echo 'Apple are $10 a dozen' >>> Apple are $10 a dozen

Note

It is impossible to embed a single quote inside single-quoted text.

- Double quotes allow variable and command substitution. The

$,`,\, and"characters have special meanings on the shell, and must be preceded by a backslash within double quotes if they are to be passed on as literal to the program:

$ echo "Hi, \" Jack \" " >>> Hi, "Jack"

- Here is an AWK example with single and double quotes:

$ awk 'BEGIN { print "Hello world" }' It can be performed as follows:

$ awk "BEGIN { print \"Hello world \" }"- Both give the same output:

Hello worldSometimes, dealing with single quotes or double quotes becomes confusing. In these instances, you can use octal escape sequences. For example:

- Printing single quotes within double quotes:

$ awk "BEGIN { print \"single quote' \" }" - Printing single quotes within single quotes:

$ awk 'BEGIN { print "single quote'\'' " }'- Printing single quotes within single quotes using the octal escape sequence:

$ awk 'BEGIN { print "single quote\47" }' - Printing single quotes using the command-line variable assignment:

$ awk -v q="'" 'BEGIN { print "single quote"q }' - All of the preceding AWK program executions give the following output:

single quote'Data files used as examples in this book

Throughout the book, most of our examples will be taking their input from two sample data files. The first one is emp.dat, which represents the sample employee information database. It consists of the following columns from left to right, each separated by a single tab:

- Employee's first name

- Last name

- Phone number

- Email address

- Gender

- Department

- Salary in USD

Jack Singh 9857532312 [email protected] M hr 2000 Jane Kaur 9837432312 [email protected] F hr 1800 Eva Chabra 8827232115 [email protected] F lgs 2100 Amit Sharma 9911887766 [email protected] M lgs 2350 Julie Kapur 8826234556 [email protected] F Ops 2500 Ana Khanna 9856422312 [email protected] F Ops 2700 Hari Singh 8827255666 [email protected] M Ops 2350 Victor Sharma 8826567898 [email protected] M Ops 2500 John Kapur 9911556789 [email protected] M hr 2200 Billy Chabra 9911664321 [email protected] M lgs 1900 Sam khanna 8856345512 [email protected] F lgs 2300 Ginny Singh 9857123466 [email protected] F hr 2250 Emily Kaur 8826175812 [email protected] F Ops 2100 Amy Sharma 9857536898 [email protected] F Ops 2500 Vina Singh 8811776612 [email protected] F lgs 2300

The second file used is cars.dat, which represents the sample car dealer database. It consists of the following columns from left to right, each separated by a single tab.

- Car's make

- Model

- Year of manufacture

- Mileage in kilometers

- Price in lakhs

The data from the file is illustrated as follows:

maruti swift 2007 50000 5 honda city 2005 60000 3 maruti dezire 2009 3100 6 chevy beat 2005 33000 2 honda city 2010 33000 6 chevy tavera 1999 10000 4 toyota corolla 1995 95000 2 maruti swift 2009 4100 5 maruti esteem 1997 98000 1 ford ikon 1995 80000 1 honda accord 2000 60000 2 fiat punto 2007 45000 3

Any other sample file, if used, will be shared in the corresponding chapter before using it in any example. Our next section demonstrates AWK command usages with examples.

Some simple examples with default usage

This section describes various useful AWK commands and their usage. We will be using the two sample files, cars.dat and emp.dat, for illustrating various useful AWK examples to kick-start your journey with AWK. Most of these examples will be short one-liners that you can include in your daily task automation. You will get the most out of this section if you practice the examples with us in your system while going through them.

Printing without pattern: The simplest AWK program can be as basic as the following:

awk { print } filename

This program consists of only one line, which is an action. In the absence of a pattern, all input lines are printed on the stdout. Also, if you don't specify any field with the print statement, it takes $0, so print $0 will do the same thing, as $0 represents the entire input line:

$ awk '{ print }' cars.datThis can also be performed as follows:

$ awk '{ print $0 }' cars.datThis program is equivalent of the cat command implemented on Linux as cat cars.dat. The output on execution of this code is as follows:

maruti swift 2007 50000 5 honda city 2005 60000 3 maruti dezire 2009 3100 6 chevy beat 2005 33000 2 honda city 2010 33000 6 chevy tavera 1999 10000 4 toyota corolla 1995 95000 2 maruti swift 2009 4100 5 maruti esteem 1997 98000 1 ford ikon 1995 80000 1 honda accord 2000 60000 2 fiat punto 2007 45000 3

Printing without action statements: In this example, the program has a pattern, but we don't specify any action statements. The pattern is given between forward slashes, which indicates that it is a regular expression:

$ awk '/honda/' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

honda city 2005 60000 3 honda city 2010 33000 6 honda accord 2000 60000 2

In this case, AWK selects only those input lines that contain the honda pattern/string in them. When we don't specify any action, AWK assumes the action is to print the whole line.

Printing columns or fields: In this section, we will print fields without patterns, with patterns, in a different printing order, and with regular expression patterns:

- Printing fields without specifying any pattern: In this example, we will not include any pattern. The given AWK command prints the first field (

$1) and third field ($3) of each input line that is separated by a space (the output field separator, indicated by a comma):

$ awk '{ print $1, $3 }' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

maruti 2007 honda 2005 maruti 2009 chevy 2005 honda 2010 chevy 1999 toyota 1995 maruti 2009 maruti 1997 ford 1995 honda 2000 fiat 2007

- Printing fields with matching patterns: In this example, we will include both actions and patterns. The given AWK command prints the first field (

$1) separated by tab (specifying\tas the output separator) with the third field ($3) of input lines, which contain themarutistring in them:

$ awk '/maruti/{ print $1 "\t" $3 }' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

maruti 2007 maruti 2009 maruti 2009 maruti 1997

- Printing fields for matching regular expressions: In this example, AWK selects the lines containing matches for the ith regular expression in them and prints the first (

$1), second ($2), and third ($3) field, separated by tab:

$ awk '/i/{ print $1 "\t" $2 "\t" $3 }' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

maruti swift 2007 honda city 2005 maruti dezire 2009 honda city 2010 maruti swift 2009 maruti esteem 1997 ford ikon 1995 fiat punto 2007

- Printing fields in any order with custom text: In this example, we will print fields in different orders. Here, in the action statement, we put the

"Mileage in kms is : "text before the$4field and the" for car model -> "text before the$1field in the output:

$ awk '{ print "Mileage in kms is : " $4 ", for car model -> " $1,$2 }' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

Mileage in kms is : 50000, for car model -> maruti swift Mileage in kms is : 60000, for car model -> honda city Mileage in kms is : 3100, for car model -> maruti dezire Mileage in kms is : 33000, for car model -> chevy beat Mileage in kms is : 33000, for car model -> honda city Mileage in kms is : 10000, for car model -> chevy tavera Mileage in kms is : 95000, for car model -> toyota corolla Mileage in kms is : 4100, for car model -> maruti swift Mileage in kms is : 98000, for car model -> maruti esteem Mileage in kms is : 80000, for car model -> ford ikon Mileage in kms is : 60000, for car model -> honda accord Mileage in kms is : 45000, for car model -> fiat punto

Printing the number of fields in a line: You can print any number of fields, such as $1 and $2. In fact, you can use any expression after $ and the numeric outcome of the expression will print the corresponding field. AWK has built-in variables to count and store the number of fields in the current input line, for example, NF. So, in the given example, we will print the number of the field for each input line, followed by the first field and the last field (accessed using NF):

$ awk '{ print NF, $1, $NF }' cars.dat The output on execution of this code is as follows:

5 maruti 5 5 honda 3 5 maruti 6 5 chevy 2 5 honda 6 5 chevy 4 5 toyota 2 5 maruti 5 5 maruti 1 5 ford 1 5 honda 2 5 fiat 3

Deleting empty lines using NF: We can print all the lines with at least 1 field using NF > 0. This is the easiest method to remove empty lines from the file using AWK:

$ awk 'NF > 0 { print }' /etc/hostsOn execution of the preceding command, only non-empty lines from the /etc/hosts file will be displayed on the Terminal as output:

# # hosts This file describes a number of hostname-to-address # mappings for the TCP/IP subsystem. It is mostly # used at boot time, when no name servers are running. # On small systems, this file can be used instead of a # "named" name server. # Syntax: # # IP-Address Full-Qualified-Hostname Short-Hostname # 127.0.0.1 localhost # special IPv6 addresses ::1 localhost ipv6-localhost ipv6-loopback fe00::0 ipv6-localnet ff00::0 ipv6-mcastprefix ff02::1 ipv6-allnodes ff02::2 ipv6-allrouters ff02::3 ipv6-allhosts

Printing line numbers in the output: AWK has a built-in variable known as NR. It counts the number of input lines read so far. We can use NR to prefix $0 in the print statement to display the line numbers of each line that has been processed:

$ awk '{ print NR, $0 }' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

1 maruti swift 2007 50000 5 2 honda city 2005 60000 3 3 maruti dezire 2009 3100 6 4 chevy beat 2005 33000 2 5 honda city 2010 33000 6 6 chevy tavera 1999 10000 4 7 toyota corolla 1995 95000 2 8 maruti swift 2009 4100 5 9 maruti esteem 1997 98000 1 10 ford ikon 1995 80000 1 11 honda accord 2000 60000 2 12 fiat punto 2007 45000 3

Count the numbers of lines in a file using NR: In our next example, we will count the number of lines in a file using NR. As NR stores the current input line number, we need to process all the lines in a file, so we will not specify any pattern. We also don't want to print the line numbers for each line, as our requirement is to just fetch the total lines in a file. Since the END block is executed after processing the input line is done, we will print NR in the END block to print the total number of lines in the file:

$ awk ' END { print "The total number of lines in file are : " NR } ' cars.dat >>> The total number of lines in file are : 12

Printing numbered lines exclusively from the file: We know NR contains the line number of the current input line. You can easily print any line selectively, by matching the line number with the current input line number stored in NR, as follows:

$ awk 'NR==2 { print NR, $0 }' cars.dat >>> 2 honda city 2005 60000 3

Printing the even-numbered lines in a file: Using NR, we can easily print even-numbered files by specifying expressions (divide each line number by 2 and find the remainder) in pattern space, as shown in the following example:

$ awk 'NR % 2 == 0 { print NR, $0 }' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

2 honda city 2005 60000 3 4 chevy beat 2005 33000 2 6 chevy tavera 1999 10000 4 8 maruti swift 2009 4100 5 10 ford ikon 1995 80000 1 12 fiat punto 2007 45000 3

Printing odd-numbered lines in a file: Similarly, we can print odd-numbered lines in a file using NR, by performing basic arithmetic operations in the pattern space:

$ awk ' NR % 2 == 1 { print NR, $0 } ' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

1 maruti swift 2007 50000 5 3 maruti dezire 2009 3100 6 5 honda city 2010 33000 6 7 toyota corolla 1995 95000 2 9 maruti esteem 1997 98000 1 11 honda accord 2000 60000 2

Printing a group of lines using the range operator (,) and NR: We can combine the range operator (,) and NR to print a group of lines from a file based on their line numbers. The next example displays the lines 4 to 6 from the cars.dat file:

$ awk ' NR==4, NR==6 { print NR, $0 }' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows :

4 chevy beat 2005 33000 2 5 honda city 2010 33000 6 6 chevy tavera 1999 10000 4

Printing a group of lines using the range operator and patterns: We can also combine the range operator (,) and string in pattern space to print a group of lines in a file starting from the first pattern, up to the second pattern. The following example displays the line starting from the first appearance of the /ford/ pattern to the occurrence of the second /fiat/ pattern in the cars.dat file:

$ awk ' /ford/,/fiat/ { print NR, $0 }' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

10 ford ikon 1995 80000 1 11 honda accord 2000 60000 2 12 fiat punto 2007 45000 3

Printing by selection: AWK patterns allows the selection of desired input lines for further processing. As patterns without actions print all the matching lines, on most occasions, AWK programs consist of a single pattern. The following are a few examples of useful patterns:

- Selection using the match operator (~): The match operator (

~) is used for matching a pattern in a specified field in the input line of a file. In the next example, we will select and print all lines containing'c'in the second field of the input line, as follows:

$ awk ' $2 ~ /c/ { print NR, $0 } ' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

2 honda city 2005 60000 3 5 honda city 2010 33000 6 7 toyota corolla 1995 95000 2 11 honda accord 2000 60000 2

- Selection using the match operator (~) and anchor (^): The caret (

^) in regular expressions (also known asanchor) is used to match at the beginning of a line. In the next example, we combine it with the match operator (~) to print all the lines in which the second field begins with the'c'character, as follows:

$ awk ' $2 ~ /^c/ { print NR, $0 } ' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

2 honda city 2005 60000 3 5 honda city 2010 33000 6 7 toyota corolla 1995 95000 2

- Selection using the match operator (~) and character classes ([ ]): The character classes,

[ ], in regular expressions are used to match a single character out of those specified within square brackets. Here, we combine the match operator (~) with character classes (/^[cp]/) to print all the lines in which the second field begins with the'c'or'p'character, as follows:

$ awk ' $2 ~ /^[cp]/ { print NR, $0 } ' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

2 honda city 2005 60000 3 5 honda city 2010 33000 6 7 toyota corolla 1995 95000 2 12 fiat punto 2007 45000 3

- Selection using the match operator (~) and anchor ($): The dollar sign (

$) in regular expression (also known as anchor) is used to match at the end of a line. In the next example, we combine it with the match operator (~) to print all the lines in the second field end with the'a'character, as follows:

$ awk ' $2 ~ /a$/ { print NR, $0 } ' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

6 chevy tavera 1999 10000 4 7 toyota corolla 1995 95000 2

- Selection by numeric comparison: You can use relation operators (

==,=>,<=,>,<,!=) for performing numeric comparison. Here, we perform a numeric match (==) to print the lines that have the2005value in the third field, as follows:

$ awk ' $3 == 2005 { print NR, $0 } ' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

2 honda city 2005 60000 3 4 chevy beat 2005 33000 2

- Selection by text content/string matching in a field: Besides numeric matches, we can use string matches to find the lines containing a particular string in a field. String content for matches should be given in double quotes as a string. In our next example, we print all the lines that contain

"swift"in the second field ($2), as follows:

$ awk ' $2 == "swift" { print NR, $0 } ' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

1 maruti swift 2007 50000 5 8 maruti swift 2009 4100 5

- Selection by combining patterns: You can combine patterns with parentheses and logical operators,

&&,||, and!, which stand for AND, OR, and NOT. Here, we print the lines containing a value greater than or equal to2005in the third field and a value less than or equal to2010in the third field. This will print the cars that were manufactured between2005and2010from thecars.datfile:

$ awk ' $3 >= 2005 && $3 <= 2010 { print NR, $0 } ' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

1 maruti swift 2007 50000 5 2 honda city 2005 60000 3 3 maruti dezire 2009 3100 6 4 chevy beat 2005 33000 2 5 honda city 2010 33000 6 8 maruti swift 2009 4100 5 12 fiat punto 2007 45000 3

Data validation: Human error is difficult to eliminate from gathered data. In this situation, AWK is a reliable tool for checking that data has reasonable values and is in the right format. This process is generally known as data validation. Data validation is the reverse process of printing the lines that have undesirable properties. In data validation, we print the lines with errors or those that we suspect to have errors.

In the following example, we use the validation method while printing the selected records. First, we check whether any of the records in the input file don't have 5 fields, that is, a record with incomplete information, by using the AWK NF built-in variable. Then, we find the cars whose manufacture year is older than 2000 and suffix these rows with the car fitness expired text. Next, we print those records where the car's manufacture year is newer than 2009, and suffix these rows with the Better car for resale text, shown as follows :

$ vi validate.awk NF !=5 { print $0, "number of fields is not equal to 5" } $3 < 2000 { print $0, "car fitness expired" } $3 > 2009 { print $0, "Better car for resale" } $ awk -f validate.awk cars.dat

The output on execution of this code is as follows :

honda city 2010 33000 6 Better car for resale chevy tavera 1999 10000 4 car fitness expired toyota corolla 1995 95000 2 car fitness expired maruti esteem 1997 98000 1 car fitness expired ford ikon 1995 80000 1 car fitness expired

BEGIN and END pattern examples: BEGIN is a special pattern in which actions are performed before the processing of the first line of the first input file. END is a pattern in which actions are performed after the last line of the last file has been processed.

Using BEGIN to print headings: The BEGIN block can be used for printing headings, initializing variables, performing calculations, or any other task that you want to be executed before AWK starts processing the lines in the input file.

In the following AWK program, BEGIN is used to print a heading for each column for the cars.dat input file. Here, the first column contains the make of each car followed by the model, year of manufacture, mileage in kilometers, and price. So, we print the heading for the first field as Make, for the second field as Model, for the third field as Year, for the fourth field as Kms, and for the fifth field as Price. The heading is separated from the body by a blank line. The second action statement, { print }, has no pattern and displays all lines from the input as follows:

$ vi header.awk BEGIN { print "Make Model Year Kms Price" ; print "" } { print } $ awk -f header.awk cars.dat

The output on execution of this code is as follows:

Make Model Year Kms Price maruti swift 2007 50000 5 honda city 2005 60000 3 maruti dezire 2009 3100 6 chevy beat 2005 33000 2 honda city 2010 33000 6 chevy tavera 1999 10000 4 toyota corolla 1995 95000 2 maruti swift 2009 4100 5 maruti esteem 1997 98000 1 ford ikon 1995 80000 1 honda accord 2000 60000 2 fiat punto 2007 45000 3

In the preceding example, we have given multiple action statements on a single line by separating them with a semicolon. The print " " prints a blank line; it is different from plain print, which prints the current input line.

Using END to print the last input line: The END block is executed after the processing of the last line of the last file is completed, and $0 stores the value of each input line processed, but its value is not retained in the END block. The following is one way to print the last input line:

$ awk '{ last = $0 } END { print last }' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

fiat punto 2007 45000 3And to print the total number of lines in a file we use NR, because it retains its value in the END block, as follows:

$ awk 'END { print "Total no of lines in file : ", NR }' cars.datThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

Total no of lines in file : 12Length function: By default, the length function stores the count of the number of characters in the input line. In the next example, we will prefix each line with the number of characters in it using the length function, as follows:

$ awk '{ print length, $0 }' /etc/passwdThe output on execution of this code is as follows:

56 at:x:25:25:Batch jobs daemon:/var/spool/atjobs:/bin/bash 59 avahi:x:481:480:User for Avahi:/run/avahi-daemon:/bin/false 79 avahi-autoipd:x:493:493:User for Avahi IPv4LL:/var/lib/avahi-autoipd:/bin/false 28 bin:x:1:1:bin:/bin:/bin/false 35 daemon:x:2:2:Daemon:/sbin:/bin/fale 53 dnsmasq:x:486:65534:dnsmasq:/var/lib/empty:/bin/false 42 ftp:x:40:49:FTP account:/srv/ftp:/bin/false 49 games:x:12:100:Games account:/var/games:/bin/false 49 lp:x:4:7:Printing daemon:/var/spool/lpd:/bin/false 60 mail:x:8:12:Mailer daemon:/var/spool/clientmqueue:/bin/false 56 man:x:13:62:Manual pages viewer:/var/cache/man:/bin/false 56 messagebus:x:499:499:User for D-Bus:/run/dbus:/bin/false .................................... ....................................

Changing the field separator using FS: The fields in the examples we have discussed so far have been separated by space characters. The default behavior of FS is any number of space or tab characters; we can change it to regular expressions or any single or multiple characters using the FS variable or the -F option. The value of the field separator is contained in the FS variable and it can be changed multiple times in an AWK program. Generally, it is good to redefine FS in a BEGIN statement.

In the following example, we demonstrate the use of FS. In this, we use the /etc/passwd file of Linux, which delimits fields with colons (:). So, we change the input of FS to a colon before reading any data from the file, and print the list of usernames, which is stored in the first field of the file, as follows:

$ awk 'BEGIN { FS = ":"} { print $1 }' /etc/passwdAlternatively, we could use the -F option:

$ awk -F: '{ print $1 }' /etc/passwdThe output on execution of the code is as follows:

at avahi avahi-autoipd bin daemon dnsmasq</strong> ftp ......... .........

Control structures: AWK supports control (flow) statements, which can be used to change the order of the execution of commands within an AWK program. Different constructs, such as the if...else, while, and for control structures are supported by AWK. In addition, the break and continue statements work in combination with the control structures to modify the order of execution of commands. We will look at these in detail in future chapters.

Let's try a basic example of a while loop to print a list of numbers under 10:

$ awk 'BEGIN{ n=1; while (n < 10 ){ print n; n++; } }'Alternatively, we can create a script, such as the following:

$ vi while1.awk BEGIN { n=1 while ( n < 10) { print n; n++; } } $ awk -f while1.awk

The output on execution of both of these commands is as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Multiple rules with AWK

AWK can have multiple pattern-action statements. They are executed in the order in which they appear in the AWK program. If one pattern-action rule matches the same linethat was matched with the previous rule, then it is printed twice. This continues until the program reaches the end of the file. In the next example, we have an AWK program with two rules:

$ awk '/maruti/ { print NR, $0 } /2007/ { print NR, $0 }' cars.dat

The output on execution of this code is as follows:

1 maruti swift 2007 50000 5 1 maruti swift 2007 50000 5 3 maruti dezire 2009 3100 6 8 maruti swift 2009 4100 5 9 maruti esteem 1997 98000 1 12 fiat punto 2007 45000 3

The record number 1 is printed twice because it matches both rule1 and rule2.

Using standard input with names in AWK

Sometimes, we may need to read input from standard input and from the pipe. The way to name the standard input, with all versions of AWK, is by using a single minus or dash sign, -. For example:

$ cat cars.dat | awk '{ print }' -This can also be performed as follows:

$ cat cars.dat | awk '{ print }' /dev/stdin ( used with gawk only )The output on execution of this code is as follows:

maruti swift 2007 50000 5 honda city 2005 60000 3 maruti dezire 2009 3100 6 chevy beat 2005 33000 2 honda city 2010 33000 6 chevy tavera 1999 10000 4 toyota corolla 1995 95000 2 maruti swift 2009 4100 5 maruti esteem 1997 98000 1 ford ikon 1995 80000 1 honda accord 2000 60000 2 fiat punto 2007 45000 3

We can also first read the input from one file, then read the standard input coming from the pipe, and then read another file again. In that case, the first file's data, the data from the pipe, and the other file's data, all become a single input. All of that data is read consecutively. In the following example, the input from cars.dat is read first, then the echo statement is taken as input, followed by the emp.dat file. Any pattern you apply in this AWK program will be applied on the whole input and not each file, as follows:

$ echo "======================================================" | \ awk '{ print NR , $0 }' cars.dat - emp.dat

The output on execution of this code is as follows:

1 maruti swift 2007 50000 5 2 honda city 2005 60000 3 3 maruti dezire 2009 3100 6 4 chevy beat 2005 33000 2 5 honda city 2010 33000 6 6 chevy tavera 1999 10000 4 7 toyota corolla 1995 95000 2 8 maruti swift 2009 4100 5 9 maruti esteem 1997 98000 1 10 ford ikon 1995 80000 1 11 honda accord 2000 60000 2 12 fiat punto 2007 45000 3 13 ====================================================== 14 Jack Singh 9857532312 [email protected] M hr 2000 15 Jane Kaur 9837432312 [email protected] F hr 1800 16 Eva Chabra 8827232115 [email protected] F lgs 2100 17 Amit Sharma 9911887766 [email protected] M lgs 2350 18 Julie Kapur 8826234556 [email protected] F Ops 2500 19 Ana Khanna 9856422312 [email protected] F Ops 2700 20 Hari Singh 8827255666 [email protected] M Ops 2350 21 Victor Sharma 8826567898 [email protected] M Ops 2500 22 John Kapur 9911556789 [email protected] M hr 2200 23 Billy Chabra 9911664321 [email protected] M lgs 1900 24 Sam khanna 8856345512 [email protected] F lgs 2300 25 Ginny Singh 9857123466 [email protected] F hr 2250 26 Emily Kaur 8826175812 [email protected] F Ops 2100 27 Amy Sharma 9857536898 [email protected] F Ops 2500 28 Vina Singh 8811776612 [email protected] F lgs 2300

Using command-line arguments: The AWK command line can have different forms, as follows:

awk 'program' file1 file2, file3 ………….

awk -f source_file file1 file2, file3 ………….

awk -Fsep 'program' file1 file2, file3 ………….

awk -Fsep -f source_file file1 file2, file3 ………….

In the given command lines, file1, file2, file3, and so on are command-line arguments that generally represent filenames.The command-line arguments are accessed in the AWK program with a built-in array called ARGV. The number of arguments in the AWK program is stored in the ARGC built-in variable, its value is one more than the actual number of arguments in the command line. For example:

$ awk -f source_file a b cHere, ARGV is AWKs' built-in array variable that stores the value of command-line arguments. We access the value stored in the ARGV array by suffixing it with an array index in square brackets, as follows:

ARGV [ 0 ]containsawkARGV [ 1 ]containsaARGV [ 2 ]containsbARGV [ 3 ]containsc

ARGC has the value of four, ARGC is one more than the number of arguments because in AWK the name of the command is counted as argument zero, similar to C programs.

For example, the following program displays the number of arguments given to the AWK command and displays their value:

$ vi displayargs.awk # echo - print command-line arguments BEGIN { printf "No. of command line args is : %d\n", ARGC-1; for ( i = 1; i < ARGC; i++) printf "ARG [ %d ] is : %s \n", i, ARGV[ i ] }

Now, we call this AWK program with the hello how are you command line argument. Here, hello is the first command line argument, how is the second, are is the third, and you is the fourth:

$ awk -f displayargs.awk hello how are youThe output on execution of the preceding code is as follows:

No. of command line args is : 4 ARG[1] is : hello ARG[2] is : how ARG[3] is : are ARG[4] is : you

The AWK commands, source filename, or other options, such as -f or -F followed by field separator, are not treated as arguments. Let's try another useful example of a command-line argument.In this program, we use command-line arguments to generate sequences of integers, as follows:

$ vi seq.awk # Program to print sequences of integers BEGIN { # If only one argument is given start from number 1 if ( ARGC == 2 ) for ( i = 1; i <= ARGV[1]; i++ ) print i # If 2 arguments are given start from first number upto second number else if ( ARGC == 3 ) for ( i = ARGV[1]; i <= ARGV[2]; i++ ) print i # If 3 arguments are given start from first number through second with a stepping of third number else if ( ARGC == 4 ) for ( i = ARGV[1]; i <= ARGV[2]; i += ARGV[3] ) print i }

Now, let's execute the preceding script with three different parameters:

$ awk -f seq.awk 10 $ awk -f seq.awk 1 10 $ awk -f seq.awk 1 10 1

All the given commands will generate the integers one through ten. Without the second argument, it begins printing the numbers from 1 to the first argument. If two arguments are given, then it prints the number starting from the first argument to the second argument. In the third case, if you specify three arguments, then it prints the numbers between the first and second argument, leaving out the third argument. The output on execution of any of these commands is as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10